When Dock Street Press in Seattle sadly said it could no longer continue, my wife, Tammy, and I decided we would dare something new. Our anniversary, November 16, 2020, will be the new publication date for Sandy and Wayne: A Novella from Southern Hollow Press.

This is the novella’s third time in print. New York Times-bestselling author Lauren Groff named Sandy and Wayne the winner of the inaugural Knickerbocker Prize, and it was edited by Heather Jacobs and published in a letter-press edition by Big Fiction. In 2016, Dock Street Press in Seattle published Sandy and Wayne: A Novella as a stand-alone book.

It was Tammy’s favorite book of all that I had been lucky enough to publish. So we were heartsick when Dock Street Press declared it couldn’t go on. Dock Street did help us get the InDesign files. We sought out and won Dean Curtis’s favor for a detail of his beautiful work on The Wild Horses of Shannon County for the cover. See his photographs at https://www.curtisphotographyllc.com/portfolio/C0000HqiN2SM6fgg/G0000z1nxeJV0Ptk

And we hired Todd Lape of Lape Designs to re-envision the whole package.

We (Southern Hollow Press) couldn’t be happier. The book will soon also be an ebook for the first time. On our anniversary, November 16, 2020, it will be available again in paperback from independent stores wherever you shop, though you’ll have to ask for it.

See https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781087918624 and support those indy stores in these tough times.

Here’s some praise Sandy and Wayne: A Novella has garnered since its first publication.

“Sandy and Wayne is tremendous, a taut, tense, magisterial work that has all the concision and sharpness of a great short story, all of the texture and detail of an engrossing novel. The novella is, in my opinion, the hardest fictional form to get right; Steve Yates has proven his mastery of this most gorgeous form.”—Lauren Groff, New York Times-bestselling author of Florida and Fates and Furies

“It’s hard to imagine a less likely setting for a love story than on a dusty Arkansas road construction crew. But this author makes it work. Sandy and Wayne are as tough and hard-nosed as they come, so their romance is touching without ever being sentimental. Yates makes great use of his insider’s knowledge of this setting. In a way, the landscape itself is the star of this story—sometimes lush, sometimes severe and threatening.”—Lisa Zeidner, author of five novels, most recently Love Bomb

“A love story with soul, without sap, Sandy and Wayne is bursting with big-hearted wisdom and an admirable empathy for its characters and setting. Call it a novella; call it a short novel; call it a long short story—it doesn’t really matter. Just be sure to call it what it is: a stunning achievement by a writer at the peak of his powers.”—Andrew Roe, author of The Miracle Girl

“Having proven himself a master of the novel and the short story, Steve Yates has set his sights on the novella. And lucky for us, his readers, that he has. Sandy and Wayne is a burst of adrenaline. At one point, as Sandy and Wayne attempt to save a man’s life, Sandy finds herself gripping Wayne’s shoulder, waiting to see if the man will open his eyes. Sandy and Wayne will grip you just that way. And won’t let go. And your eyes will be opened.”—David James Poissant, author of Lake Life and The Heaven of Animals

“What a rare thing: a book that’s as compelling and complex a story about work as it is about love (and it’s a pretty great love story).”—Tom Nissley, author of A Reader’s Book of Days

“Sandy and Wayne is a gripping, white-hot novella about unlikely heroes, marginal but crucial characters who build the roads to where we want to go. They are like ‘them people’ in the Bible who are never named, and these two just happen to fall in love despite themselves. Steve Yates takes on unusual, fresh material here—the rough lonely jobs of highway workers who gather in dark pool halls at the end of dusty days to drink and imagine a better life. There is the muscular language of hard highway work, the everyday violence of living in the Ozarks, and the landscape filled with cigarette smoke, Peterbilts, Caterpillar earthmovers, and decaying motor lodges.”—Margaret McMullan, Clarion Ledger / Hattiesburg American Mississippi Books Page

At the end of Sandy and Wayne, in the acknowledgments, I say “And unending, boundless thanks to my wife, Tammy Gebhart Yates, for believing always in me, even when I did not.” Her relentless love and pressure made this anniversary gift happen. Love you, Adventure Girl!

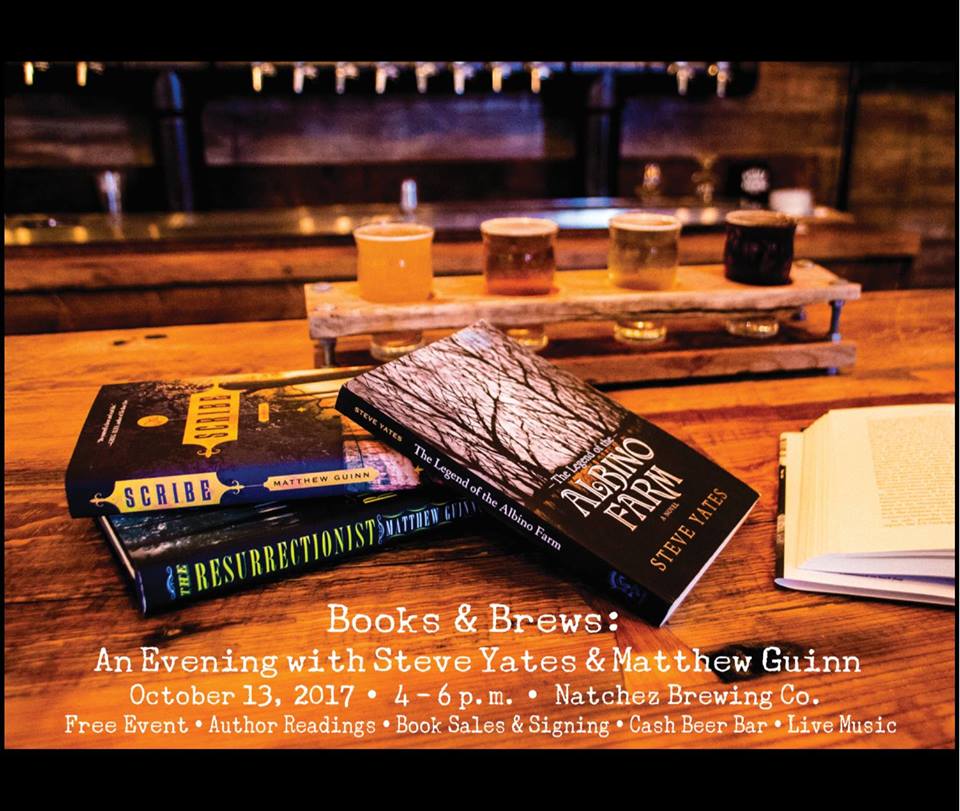

WHAT: Matthew Guinn and Steve Yates preview the 2018 Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration and introduce the theme, Southern Gothic

WHAT: Matthew Guinn and Steve Yates preview the 2018 Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration and introduce the theme, Southern Gothic In writing

In writing

we launched The Legend of the Albino Farm: A Novel at the

we launched The Legend of the Albino Farm: A Novel at the

In addition to the two library lectures, successful signings happened at BookMarx and at Barnes & Noble-Springfield, where Reneé has been a supporter of every book I have published. Nightbird Books in Fayetteville, Arkansas, also had a happy turnout and a nearly full room. It was great to see old friends and meet new readers! The photograph above is by Allis Hammond of the

In addition to the two library lectures, successful signings happened at BookMarx and at Barnes & Noble-Springfield, where Reneé has been a supporter of every book I have published. Nightbird Books in Fayetteville, Arkansas, also had a happy turnout and a nearly full room. It was great to see old friends and meet new readers! The photograph above is by Allis Hammond of the